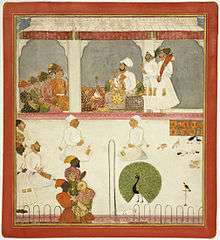

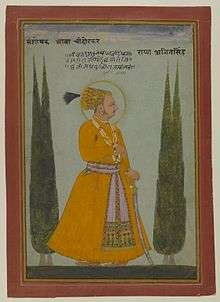

Ajit Singh of Marwar

| Ajit Singh | |

|---|---|

Ajit Singh | |

| Tenure | 1699 - 1724 |

| Born |

c. 1679 Lahore |

| Died |

24 June 1724 Meherangarh, Jodhpur |

| Issue |

Abhai Singh Bakht Singh |

| Father | Jaswant Singh |

| Mother | Jadaman |

| Religion | Hinduism |

Ajit Singh (c. 1679 – 24 June 1724) was a ruler of the Marwar region in the present-day Rajasthan and the son of Jaswant Singh.

Early years

Jaswant Singh of Marwar died at Jamrud in December 1678. His two wives were pregnant but, There being no living male heir, the lands in Marwar were converted by the emperor Aurangzeb into territories of the Mughal empire so that they could be managed as jagirs. He appointed Indra Singh Rathor, a nephew of Jaswant Singh, as ruler there.[lower-alpha 1] Historian John F. Richards stresses that this was intended as a bureaucratic exercise rather than an annexation.[1]

There was opposition to Aurangzeb's actions because both pregnant women gave birth to sons during the time that he was enacting his decision. In June 1679, Durgadas Rathor, a senior officer of the former ruler, led a delegation to Shahjahanabad where they pleaded with Aurangzeb to recognise the older of these two sons, Ajit Singh, as successor to Jaswant Singh and ruler of Marwar. Aurangzeb refused, offering instead to raise Ajit and to give him the title of raja, with an appropriate noble rank, when he attained adulthood. However, the offer was conditional on Ajit being brought up as a Muslim, which was anathema to the petitioners.[1][2]

The dispute escalated when Ajit Singh's younger brother died. Aurangzeb sent a force to capture the two queens and Ajit from the Rathor mansion in Shahjahanabad but his attempt was rebuffed by Durgadas Rathor, who initially used gunfire in retaliation and eventually escaped from the city to Jodhpur along with Ajit and the two queens, who were disguised as men. Some of those accompanying the escapees detached themselves from the party and were killed as they fought to slow down the pursuing Mughals.[1]

A slave girl was left behind at the mansion and passed off her own young child as being Ajit. Aurangzeb deigned to accept this deceit and sent the child to be raised as a Muslim in his harem. The child was renamed Mohammadi Raj and the act of changing religion meant that, by custom, the imposter lost all hereditary entitlement to the lands of Marwar that he would otherwise have had if he had indeed been Ajit Singh.[1][3]

Exile

Continuing to play along with the deceit, Aurangzeb refused to negotiate with representatives of Ajit Singh, claiming that child to be the imposter.[3] He sent his son, Muhammad Akbar, to occupy Marwar. Ajit Singh's mother, who was a Sisodia, convinced the Rana of Mewar, Raj Singh I, who is commonly thought to be her relative, to join in fighting against the Mughals. Richards says that Raj Singh's fear that Mewar would also be invaded was a major motivation for becoming involved; another historian, Satish Chandra, thinks that there were several possible alternatives, including Singh seeing an opportunity to assert Mewar's position among the Rajput principalities of the region. The combined Rathor-Sisodia forces were no match for the Mughal army, Mewar was itself attacked and the Rajputs had to retire to the hills, from where they engaged in sporadic guerrilla warfare.[1][3][lower-alpha 2]

For 20 years after this event, Marwar remained under the direct rule of a Mughal governor. During this period, Durgadas Rathor carried out a relentless struggle against the occupying forces. Trade routes that passed through the region were plundered by the guerrillas, who also looted various treasuries in present-day Rajasthan and Gujarat. These disorders adversely impacted the finances of the empire.

Aurangzeb died in 1707; he was to prove the last of the great Mughals. Durgadas Rathor took advantage of the disturbances following this death to seize Jodhpur and eventually evict the occupying mughal force.[4]

Takes charge of Marwar

The rebellious Ajit Singh was pardoned in 1708.[5] In 1712 Ajit Singh was given more power with his appointment as Mughal governor of Gujarat.[6]

In 1713 the new Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar appointed Ajit Singh governor of Thatta. Ajit Singh refused to go to this distant province and Farrukhsiyar sent Husain Ali Braha to bring Ajit Singh into line, but also sent a private letter to Ajit Singh promising him blessings if he defeated Husain. Instead Ajit Singh chose to negotiate with Husain, accepting the governorship of Thatta with a promise for a return to Gujarat in the near future.[7]

Another result of this treaty was plans for Ajit Singh's daughter to marry the emperor. This occurred in December 1715.[8]

Patricide

After he was killed by his son Bakhat Singh in 1724, he was succeeded by his eldest son Abhai Singh of Marwar.

The practice of sati was common among Rajput nobility in the region: six queens, 25 concubines and 32 female slaves were burned on Ajit Singh's funeral pyre. Unusually, three male advisors also self-immolated.[9]

References

Notes

- ↑ Some sources say that Indra Singh Rathor was a great-nephew of Jaswant Singh.

- ↑ The relationship of Raj Singh I to Ajit Singh's mother is disputed. Historian Satish Chandra says that, although the claim is often made, they were unrelated.[3]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-52156-603-2.

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 189. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Chandra, Satish (2005). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals. 2. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-8-12411-066-9.

- ↑ N.S. Bhati, Studies in Marwar History, page 6

- ↑ Faruqui, Munis D. (2012). The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504-1719. Cambridge University Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-1-107-02217-1.

- ↑ Richards, The Mughal Empire, p. 262

- ↑ Richards, The Mughals, p. 166

- ↑ Richards, The Mughals, p. 268

- ↑ Major, Andrea (2010). Sovereignty and Social Reform in India: British Colonialism and the Campaign Against Sati, 1830-1860. Routledge. pp. 33, 127. ISBN 978-1-13690-115-7.

Further reading

- Gupta, R. K.; Bakshi, S. R., eds. (2008). Studies In Indian History: Rajasthan Through The Ages: The Heritage Of Rajputs. 1. Sarup & Sons. ISBN 978-8-17625-841-8.