Airbus A400M Atlas

| A400M Atlas | |

|---|---|

| |

| The second prototype A400M, Grizzly 2, at the 2010 Farnborough Airshow | |

| Role | Strategic/tactical airlift |

| Manufacturer | Airbus Defence and Space |

| First flight | 11 December 2009[1] |

| Introduction | 2013 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | French Air Force Royal Air Force German Air Force Turkish Air Force See Operators below for others |

| Produced | 2007–present |

| Number built | 38 |

| Unit cost |

€152.4m[2](FY 2013) (France) |

The Airbus A400M Atlas[3][4] is a multi-national, four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft. It was designed by Airbus Military (now Airbus Defence and Space) as a tactical airlifter with strategic capabilities to replace older transport aircraft, such as the Transall C-160 and the Lockheed C-130 Hercules.[5] The A400M is positioned, in terms of size, between the C-130 and the C-17; it can carry heavier loads than the C-130, while able to use rough landing strips. Along with the transport role, the A400M can perform aerial refuelling and medical evacuation when fitted with appropriate equipment.

The A400M's maiden flight, originally planned for 2008, took place on 11 December 2009 from Seville, Spain.[1] Between 2009 and 2010, the A400M faced cancellation as a result of development program delays and cost overruns; however, the customer nations chose to maintain their support of the project. A total of 174 A400M aircraft have been ordered by eight nations as of July 2011.[6] In March 2013, the A400M received European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) certification. The first aircraft was delivered to the French Air Force in August 2013.

Development

Origins

The project began as the Future International Military Airlifter (FIMA) group, set up in 1982 by Aérospatiale, British Aerospace (BAe), Lockheed, and Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm (MBB) to develop a replacement for the C-130 Hercules and Transall C-160.[7] Varying requirements and the complications of international politics caused slow progress. In 1989, Lockheed left the grouping and went on to develop an upgraded Hercules, the C-130J Super Hercules. With the addition of Alenia of Italy and CASA of Spain the FIMA group became Euroflag.

Since no existing turboprop engine in the western world was powerful enough to reach the projected cruise speed of Mach 0.72, a new engine design was required. Originally the SNECMA M138 turboprop (based on the M88 core) was selected, but didn't meet the requirements.[8] Airbus Military issued a new request for proposal (RFP) in April 2002, after which Pratt & Whitney Canada with the PW180 and Europrop International answered. In May 2003, Airbus Military selected the Europrop TP400-D6, reportedly due to political interference over the PW180 engine.[9][10]

The original partner nations were France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, Turkey, Belgium, and Luxembourg. These nations decided to charge the Organisation for Joint Armament Cooperation (OCCAR) with the management of the acquisition of the A400M. Following the withdrawal of Italy and revision of procurement totals the revised requirement was for 180 aircraft, with first flight in 2008 and first delivery in 2009. On 28 April 2005, South Africa joined the partnership programme with the state-owned Denel Saab Aerostructures receiving a contract for fuselage components.[11]

The A400M is positioned as an intermediate size and range between the Lockheed C-130 and the Boeing C-17, carrying cargo too heavy for the C-130 while able to use rough landing strips.[12] It has been advertised with the tagline "transport what the C130 cannot to places that the C17 can’t".[13]

Delays and problems

On 9 January 2009, EADS announced that the first delivery was postponed until at least 2012, and indicated that it wanted to renegotiate "certain technical characteristics".[14] EADS maintained the first deliveries would begin three years after the A400M's first flight. On 12 January 2009, the German newspaper Financial Times Deutschland reported that the A400M was overweight by 12 tons and may not achieve a critical performance requirement, the ability to airlift 32 tons; sources told FTD at the time that the aircraft could only lift 29 tons, which is insufficient to carry a modern armored infantry fighting vehicle, like the Puma.[15] In response to the FTD report, the chief of the German Air Force stated: "That is a disastrous development," and could delay deliveries to the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) until 2014.[16] The Initial Operational Capability (IOC) for the Luftwaffe is delayed at least until 2017, leading to political planning of potential alternatives such as a higher integration of European airlift capabilities.[17]

On 29 March 2009, Airbus CEO Thomas Enders told Der Spiegel magazine that the program might need to be abandoned without changes.[18] The OCCAR reminded the participating countries that they can terminate the contract before 31 March 2009.[19] On 3 April 2009 the South African Air Force announced that it would start considering alternatives to the A400M due to postponed production and increased cost.[20] On 5 November 2009, South Africa announced it was cancelling the order citing increased cost and delivery delays.[21] On 12 June, The New York Times reported that Germany and France had delayed the decision whether or not to cancel their orders for another six months, while the UK still planned to decide at the end of June. The NYT also quoted a report to the French Senate from February 2009, according to which "the A400M is €5 billion over budget, 3 to 4 years behind schedule, [...] aerospace experts estimate it is also costing Airbus between €1 billion and €1.5 billion a year."[22]

In 2009, Airbus acknowledged that the program was expected to lose at least €2.4 billion and cannot break even without sales outside NATO countries.[9] A PricewaterhouseCoopers audit projected that the program would run €11.2 billion over budget, and that corrective measures would result in an overrun of €7.6 billion.[23] On 24 July 2009, the seven European nations announced that the program would proceed and formed a joint procurement agency to renegotiate the contract.[24][25] On 9 December 2009, the Financial Times reported that Airbus requested an additional €5 billion subsidy for the project.[26] On 5 January 2010, Airbus repeated that the A400M may be scrapped, costing Airbus €5.7 billion unless €5.3 billion was added by partner governments.[27] On 11 January 2010, Tom Enders, Airbus chief executive, stated that he was prepared to cancel the A400M if European governments did not provide more funding; delays had already increased its budget by 25%.[28] Airbus executives reportedly regarded the A400M as a drain on resources that could have gone towards the A380 or A350 XWB programs, and even considered spinning off the military division as a separate company.[29]

A shortage of military transports caused by the delay of the A400M programme led the UK to lease C-17s in 2001 and eventually purchase eight of the aircraft. France and Germany also considered other aircraft, as all three countries needed support operations in Afghanistan.[30][31] The C-17 gives the RAF additional strategic capabilities such as a maximum payload of 169,500 lb (77,000 kg) compared to the A400M's 82,000 lb (37,000 kg).[32][32] In June 2009, Lockheed Martin said that both the UK and France had asked for technical details on the C-130J as an alternative to the A400M.[33] In 2011, the ADS Group warned that shifting British orders to American aircraft for short term budget savings would cost much more over time in missed civil and military aerospace business, stating that technologies used in the A400M would be a bridge to the next generation of civilian aircraft.[34]

On 5 November 2010, Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Spain and Turkey finalised the contract and agreed to lend Airbus Military €1.5 billion. The program was then at least three years behind schedule. The UK reduced its order from 25 to 22 aircraft and Germany from 60 to 53, decreasing the total order from 180 to 170.[35] In October 2012, John Gilbert, Britain's former Minister for Defence Procurement, stated in the British House of Lords "The A400M is a complete, absolute wanking disaster, and we should be ashamed of ourselves. I have never seen such a waste of public funds in the defence field since I have been involved in it these past 40 years."[36][37]

In 2013, France's budget for 50 aircraft was €8.9bn (~US$11.7bn) at a unit cost of €152.4m (~US$200m), or €178m (~US$235m) including development costs.[2] The 2013 French White Paper on Defence and National Security cut their requirement for tactical transport aircraft from 70 to 50, including aircraft for use by special forces.[38] As the A400M was still unable to perform in-flight refuelling for helicopters, France announced in 2016 that it would also purchase four C-130J aircraft for special forces support and helicopter aerial refueling.[39] In July 2016, French aerospace laboratory ONERA confirmed that it had successfully trialled a 36.5m (120ft) hose and drogue configuration in a wind tunnel to permit helicopter refuelling from the airlifter. Earlier flight tests had demonstrated that the intended 24m (80ft) hose was unstable due to the vortices generated by the deployment of the A400M’s spoilers to achieve the required 108-130kt air speed. New flight tests are to be conducted later in 2016 to validate the findings.[40]

On 1 April 2016, ADS confirmed that it was working to resolve manufacturing faults affecting fourteen propeller gear boxes (PGBs) produced by TP400 supplier Europrop International (EPI) in the first half of 2015. The gearboxes are made by Italian supplier Avio Aero, owned by General Electric. The issue involved a specific heat treatment process in manufacturing that adversely affected the strength of the ring gear; no other PGBs before or since were affected and the units involved either have been or are being changed. Airbus noted that "pending full replacement of the batch, any aircraft can continue to fly with no more than one affected propeller gear box installed and is subject to continuing inspections." Another PGB issue involves cracking of the input pinion plug, which in some cases can result in the release of small metallic particles into the oil system, where they are detected by a magnetic chip detector. Only engines 1 and 3, which have propellers that rotate to the right, are affected. The European Aviation Safety Agency has issued an Airworthiness Directive mandating immediate on-wing inspection, followed by replacement if evidence of damage is found, or else return-to-service and continuing inspections.[41][42] On 27 April 2016, when delivering Q1 2016 financial results, Airbus warned there could be a significant cost in repairing the gearbox.[43] In June 2016, two German A400Ms – aircraft 54-01 (received in December 2014) and 54-02 (received in December 2014) – were temporarily grounded after inspections found heavy engine wear in the clockwise rotation PGBs after only 365 and 189 hours of operations respectively.[44] An interim fix for this PGB issue was certified in July 2016, which extends the inspection phase from 100 hours to 650 hours, with follow-up inspections every 150 hours, up from 20 hours.[45]

On 13 May 2016, Airbus confirmed that an unknown cracking behaviour that had already been identified during quality control checks in 2011 was found in an aluminium fuselage part of a French A400M; the issue did not affect flight safety and repairs could be incorporated into regular maintenance and upgrade schedules.[46][47] The aluminum alloy, known as 7X6, has been used in a number of frames in the aircraft’s centre; the alloy’s chemistry, along with environmental conditions, resulted in small cracks propagating into the frames. A decision has been made to exclude the material from MSN70 onwards, an aircraft that will emerge from the production line in 2017. A retrospective process to remove the material from aircraft already in service is now being defined. The swap could take up to seven months.[48]

On 29 May 2016, Airbus chief Tom Enders conceded in an interview published in Bild am Sonntag that some of the "massive problems" dogging the A400M were of the group’s own making. He said "We underestimated the engine problems" and "Airbus had let itself be persuaded by some well-known European leaders into using an engine made by an inexperienced consortium." Furthermore, it had let itself be roped into assuming full responsibility for this new type of turbo-prop engine, he continued. "These are two massive problems which we’re now paying for."[49] On 27 July 2016 Airbus confirmed that it had taken a $1 billion financial charge on the A400M programme, in the light of delivery problems and export market prospects. It noted that “Commercial negotiations with OCCAR and the nations are yet to take place with regard to the revised delivery schedule and its implications.”[50] Tom Enders commented “Industrial efficiency and the step-wise introduction of the A400M’s military functionalities are still lagging behind schedule and remain challenging.” [51]

Flight testing

Before the first flight, the required airborne test time on the Europrop TP400 engine was gained using a Lockheed C-130 testbed aircraft, which first flew on 17 December 2008.[52][53] On 11 December 2009, the A400M's maiden flight was carried out from Seville.[1] By March 2010, the first A400M had flown 39 hours of test flights.[54] On 8 April 2010, the second A400M made its first flight.[55] In July 2010, the third A400M took to the air, at which point the fleet had flown 400 hours over more than 100 flights.[56] In July 2010, the A400M passed a key test – ultimate-load testing of the wing.[57] On 28 October 2010, Airbus announced that it was to start refuelling and air-drop tests.[58] By October 2010, the A400M had flown 672 hours of the 2,700 hours expected to reach certification.[59] In November 2010, the first paratroop jumps were performed; Airbus CEO Tom Enders and A400M project manager Bruno Delannoy were among the skydivers.[60][61] By December 2010, the total fleet flight time had risen to 965 hours.[62] A fourth A400M made its first flight on 20 December 2010.[63]

In late 2010, simulated icing tests were performed on the MSN1 flight test aircraft using devices installed on the leading edges of the wing.[64] These revealed an aerodynamic issue causing buffeting of the horizontal tail, necessitating a six-week retrofit to install anti-icing equipment fed with engine bleed air;[64] production aircraft are to be similarly fitted.[64] Winter tests were done in Kiruna, Sweden during February 2011.[65] In March 2012, high altitude start and landing tests were performed at La Paz at 4,061.5 m (13,325 ft) and Cochabamba at 2,548 m (8,360 feet) in Bolivia.[66][67][68]

By April 2011, a total of 1,400 flight hours over 450 flights had been achieved.[69] In May 2011, the A400M's EPI TP400-D6 engine received certification from the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA).[70] In May 2011, the A400M fleet had totaled 1,600 hours over 500 flights; by September 2011, the total increased to 2,100 hours and 684 flights.[71] Due to a gearbox problem, an A400M was shown on static display instead of a flight demonstration at the 2011 Paris Air Show.[72] By October 2011, the total flight hours had reached 2,380 over 784 flights.[73]

During May 2012, the MSN2 flight test aircraft was due to spend a week conducting unpaved runway trials on a grass strip at Cottbus-Drewitz Airport in Germany.[74] Testing was cut short on 23 May, when, during a rejected takeoff test, the left side main wheels broke through the runway surface. Airbus Military stated that it found the aircraft's behaviour was "excellent". The undamaged aircraft returned to Toulouse.[74]

On 14 March 2013, the A400M received its Type Certification from the European Aviation Safety Agency.[75]

Production and delivery

Assembly of the first A400M began at the Seville plant of EADS Spain in early 2007. Major assemblies built at other facilities abroad were brought to the Seville facility by Airbus Beluga transporters. In February 2008, four Europrop TP400-D6 flight test engines were delivered for the first A400M.[76] Static structural testing of an A400M test airframe began on 12 March 2008 in Spain.[77] By 2010, Airbus planned to manufacture 30 aircraft per year.[78]

The first flight, originally scheduled for the first quarter of 2008, was postponed due to program delays, schedule adjustments and financial pressures. EADS announced in January 2008 that development problems with the engines had resulted in a delay to the second quarter of 2008 before the first engine test flights on a C-130 testbed aircraft. The first flight of the aircraft, previously scheduled for July 2008, was again postponed. Civil certification under European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) CS-25 will be followed later by certification for military purposes. The A400M was "rolled out" in Seville on 26 June 2008 at an event presided by King Juan Carlos I of Spain.[79]

On 12 January 2011, serial production of the A400M formally commenced.[80] On 1 August 2013, delivery of the first aircraft to the French Air Force, it was formally handed over during a ceremony on 30 September 2013.[81][82] On 9 August 2013, the first Turkish A400M conducted its maiden flight from Seville,[83] and in March 2015 Malaysia took delivery of its first A400M.[84]

In May 2015, a German defense ministry letter revealed that the member countries had established a Program Monitoring Team (PMT) to analyze and judge Airbus plans to bring the A400M on track. As well as monitoring progress in development and production, the PMT schedules on-site visits to the final assembly line in Seville, Spain, and other production facilities. The PMT's first conclusions on program recovery include an observation that Airbus lacked an integrated approach to production, development and retrofits, treating these as separate programs.[85]

On 9 May 2015, an A400M crashed in Seville on its first production test flight.[86] Germany, Malaysia, Turkey and UK suspended A400M flights during the investigation.[87][88] Initial focus was on whether the crash was caused by new fuel supply management software, designed to trim the fuel tanks to enable certain military maneuvers; Airbus issued an update instructing operators to inspect all Engine Control Units (ECUs).[89] A key scenario examined by investigators is that the torque calibration parameter data was accidentally wiped on three engines as the software was being installed, preventing FADEC operations. As designed, the first warning of an engine data problem would occur when the plane was 120 meters (400 feet) in the air; on the ground, there is no cockpit alert.[90] On 3 June 2015, Airbus announced that investigators had confirmed "that engines one, two and three experienced power frozen after lift-off and did not respond to the crew's attempts to control the power setting in the normal way."[91]

On 11 June 2015, Spain's Ministry of Defense announced that A400M prototypes could restart test flights and confirmed that its specialist aerospace unit had met with Airbus to discuss flight permits, and that further permits relating to the program could be granted in the coming days.[92] The RAF lifted its suspension on A400M flights "following certain checks and extra procedures" on 16 June 2015, followed the next day by the Turkish Air Force.[93] On 19 June 2015, deliveries restarted; the first aircraft, MSN019, is the seventh to be delivered to France and the 13th to be delivered in all. The FAL has also completed the build of four aircraft for the United Kingdom, which will now undergo pre-delivery checks and trials before being flown to Royal Air Force (RAF) Brize Norton in Oxfordshire.[94]

In June 2016 the French Air Force accepted its ninth A400M – MSN33 – the first capable of conducting tactical tasks such as the airdrop of supplies. The revised standard includes the addition of cockpit armour and defensive aids system equipment, plus clearance for the Atlas to transfer and receive fuel in-flight.[95]

Airbus has been working to develop a Future Maritime Patrol (MPA) version and airborne refuelling (AAR) variant for the A400M.

Design

The Airbus A400M increases the airlift capacity and range compared with the aircraft it was originally set to replace, the older versions of the Hercules and Transall. Cargo capacity is expected to double over existing aircraft, both in payload and volume, and range is increased substantially as well. The cargo box is 17.71 m long excluding ramp, 4.00 m wide, and 3.85 m high (or 4.00 m aft of the wing).[96] The A400M operates in many configurations including cargo transport, troop transport, and medical evacuation. The aircraft is intended for use on short, soft landing strips and for long-range, cargo transport flights.[97]

It features a fly-by-wire flight control system with sidestick controllers and flight envelope protection. Like other Airbus aircraft, the A400M has a full glass cockpit. Most of the aircraft systems are loosely based on those of the A380, but modified for the military mission. The hydraulic system has dual 3,000-psi channels powering the primary and secondary flight-control actuators, landing gear, wheel brakes, cargo door and optional hose-and-drogue refueling system. As with the A380, there is no third hydraulic system. Instead, there are two electrical systems; one is a set of dual-channel electrically powered hydraulic actuators, the other an array of electrically/hydraulically powered hybrid actuators. The dissimilar redundancy provides more protection against battle damage.[98]

.jpg)

The A400M's wings are primarily carbon fibre reinforced plastic. The eight-bladed scimitar propeller is also made from a woven composite material. The aircraft is powered by four Europrop TP400-D6 engines rated at 8,250 kW (11,000 hp) each.[99] The TP400-D6 engine is to be the most powerful turboprop engine in the West to enter operational use.[70]

The pair of propellers on each wing of the A400M turn in opposite directions, with the tips of the propellers advancing from above towards the midpoint between the two engines. This is in contrast to the overwhelming majority of multi-engine propeller driven aircraft where all propellers turn in the same direction. The counter-rotation is achieved by the use of a gearbox fitted to two of the engines, and only the propeller turns the opposite direction; all four engines are identical and turn in the same direction. This eliminates the need to have two different "handed" engines on stock for the same aircraft, simplifying maintenance and supply costs. This configuration, dubbed down between engines (DBE), allows the aircraft to produce more lift and lessens the torque and prop wash on each wing. It also reduces yaw in the event of an outboard engine failure.[100]

A forward-looking infrared enhanced vision system (EVS) camera provides an enhanced terrain view in low-visibility conditions. The EVS imagery is displayed on the HUD for low altitude flying, demonstrating its value for flying tactical missions at night or in clouds.[98] EADS and Thales provides the new Multi-Colour Infrared Alerting Sensor (MIRAS) missile warning sensor for the A400M.[101][102]

The A400M has a removable refuelling probe mounted above the cockpit to allow the aircraft to receive fuel from drogue-equipped tankers.[103] Optionally, the receiving probe can be replaced with a fuselage mounted UARRSI receptacle for receiving fuel from boom equipped tankers.[104] The aircraft can also act as a tanker when fitted with two wing mounted hose and drogue under-wing refuelling pods or a centre-line Hose and Drum unit.[103]

The A400M features deployable baffles in front of the rear side doors, intended to give paratroops time to get clear of the aircraft before they are hit by the slipstream.[105]

Operational history

On 29 December 2013, the French Air Force performed the A400M's first operational mission, the aircraft having flown to Mali in support of Operation Serval.[106][107]

On 10 September 2015, the RAF was declared the A400M fleet leader in terms of flying hours, with 900 hours flown over 300 sorties, achieved by a fleet of four aircraft. Sqn. Ldr. Glen Willcox of the RAF's Heavy Aircraft Test Squadron confirmed that reliability levels were high for an aircraft so early in its career, and that night vision goggle trials, hot and cold soaking, noise characterization tests and the first tie-down schemes for cargo had already been completed. In March 2015, the RAF's first operational mission occurred flying cargo to RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus.[108]

Exports

- South Africa

In December 2004, South Africa announced it would purchase eight A400Ms at a cost of approximately €837 million, with the nation joining the Airbus Military team as an industrial partner. Deliveries were expected from 2010 to 2012.[109][110] In 2009, South Africa cancelled all eight aircraft, citing increasing costs. On 29 November 2011 Airbus Military reached an agreement to refund pre-delivery payments worth €837 million to Armscor.[111]

- Others

In July 2005, the Chilean Air Force signed a Memorandum of understanding for three aircraft,[112] but no order has been placed; Chile began talks on buying the Brazilian Embraer KC-390.[113]

In December 2005, the Royal Malaysian Air Force ordered four A400Ms to supplement its fleet of C-130 Hercules.[114][115]

Variants

%2C_54%2B01%2C_Airbus_A400M_(22550413067).jpg)

- A400M Grizzly

- Five prototype and development aircraft, a sixth aircraft was cancelled.

- A400M-180 Atlas

- Production variant

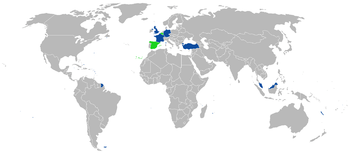

Operators

As of 31 October 2016[116]

| Date | Country | Orders | Deliveries | Entry into service date |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 May 2003 | 53 | 5 | December 2014 | Order reduced from 60 to 53 (plus 7 options),[117] and will try to resell 13, and leave 40 for German use.[118] | |

| 50 | 10 | August 2013 | Two aircraft delivered in 2013;[119] four more delivered during 2014.[120] | ||

| 27 | 1[121] | November 2016 | Original budget of €3,453M increased to €5,493M in 2010.[122] Requirement reduced to 14 aircraft and will try to resell the remaining 13.[123] | ||

| 22 | 12 | November 2014[124] | Order reduced from 25 to "at least 22".[125] | ||

| 10 | 3 | April 2014[126][127] | A400M deliveries to be completed by 2018.[128][129] Second aircraft delivered in 2014.[130] | ||

| 7 | 0 | Expected 2018–2020 | |||

| 1 | 0 | Expected 2019 | To be stationed in Belgium as a part of a bi-national fleet.[131] | ||

| 8 December 2005 | 4[114] | 3[132] | March 2015[84] | Only non-European country to purchase the A400M. Deliveries began in March 2015.[84] | |

| Total: | 174 | 33 |

Accidents

The first crash of an A400M occurred on 9 May 2015, when aircraft MSN23,[133] on its first test flight crashed shortly after take-off from San Pablo Airport in Seville, Spain, killing four Spanish Airbus crew members and seriously injuring two others. Once airborne, the crew had contacted air traffic controllers just before the crash about a technical failure,[134][135] and collided with an electricity pylon while attempting an emergency landing.[136] One of the survivors told investigators that "the aircraft suffered multiple engine failures."[137] The aircraft had been scheduled for delivery to the Turkish Air Force.[138] The crash was later attributed to the FADEC being unable to properly read engine sensors due to an accidental file-wipe, leading to three of its four propeller engines remaining in 'Idle' mode during takeoff.[139]

Specifications

Data from Airbus Defence & Space specifications[140]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3 or 4 (2 pilots, 3rd optional, 1 loadmaster)

- Capacity: 37,000 kg (81,600 lb)

- 116 fully equipped troops / paratroops,

- up to 66 stretchers accompanied by 25 medical personnel

- cargo compartment: width 4.00-metre (13.12 ft) x height 3.85-metre (12.6 ft) x length 17.71-metre (58.1 ft) (without ramp 5.40-metre (17.7 ft))

- Length: 45.1 m (148 ft 0 in)

- Wingspan: 42.4 m (139 ft 1 in)

- Height: 14.7 m (48 ft 3 in)

- Wing area: 225.1 m2 (2,423 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 76,500 kg (168,654 lb) ; operating weight[141]

- Gross weight: 120,000 kg (264,555 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 141,000 kg (310,852 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 50,500 kg (111,300 lb) internal fuel

- Max landing weight: 123,000 kg (271,200 lb)

- Powerplant: 4 × Europrop TP400-D6 turboprop, 8,200 kW (11,000 hp) each

- Propellers: 8-bladed Ratier-Figeac FH385 and FH386 variable pitch tractor propellers with feathering and reversing capability (FH385 anticlockwise on engines 2 and 4, FH386 clockwise on engines 1 and 3)[142], 5.3 m (17 ft 5 in) diameter

Performance

- Cruising speed: 781 km/h (485 mph; 422 kn) at 9,450 m (31,000 ft)[98]

- Initial cruise altitude: 9,000 m (29,000 ft) at MTOW

- Range: 3,300 km (2,051 mi; 1,782 nmi) at max payload (long range cruise speed; reserves as per MIL-C-5011A)

- Range at 30-tonne payload: 4,500 km (2,450 nmi)

- Range at 20-tonne payload: 6,400 km (3,450 nmi)

- Ferry range: 8,700 km (5,406 mi; 4,698 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 12,200 m (40,026 ft)

- Tactical takeoff distance: 980 m (3,215 ft), aircraft weight 100 tonnes (98 long tons; 110 short tons), soft field, ISA, sea level

- Tactical landing distance: 770 m (2,530 ft) (as above)

- Turning radius (ground): 28.6 m

See also

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Antonov An-70 – four propfans

- Embraer KC-390 – two jet engines

- UAC/HAL Il-214 – two jet engines

- Kawasaki C-2 – two jet engines

- Lockheed Martin C-130J Super Hercules – four turboprops

- Shaanxi Y-9 – four turboprops

- Tupolev Tu-330 – two jet engines

References

- 1 2 3 "Updated- Pictures & Video: Airbus celebrates as A400M gets airborne". Flight International. 11 December 2009. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009.

- 1 2 "Projet de loi de finances pour 2014 : Défense : équipement des forces" (in French). Senate of France. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 2014-08-30.

- ↑ "A400M naming ceremony at RIAT." Airbus Military, 6 July 2012. Retrieved: 6 July 2012.

- ↑ Hoyle, Craig. "RIAT: A400M reborn as 'Atlas'." Flightglobal 6 July 2012. Retrieved: 6 July 2012.

- ↑ "RAF – A400m." RAF, MOD. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ "A400M Contract Amendment Finalised With Customer Nations." Airbus Military. Retrieved: 9 September 2011.

- ↑ Hewson, R. The Vital Guide to Military Aircraft, 2nd ed. Airlife Press, Ltd. 2001.

- ↑ A400M: engines. Tracing the tangled roots. Flight International, 9–15 November 2004, p. 59, 60.

- 1 2 "Airbus Transport Is Almost Ready for Takeoff ". Wall Street Journal, 2 December 2009.

- ↑ Reed Business Information Limited. "USA blasts A400M engine choice". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ "South Africa to Cancel its A400M Order." Defense Industry Daily. Retrieved: 2 May 2012.

- ↑ "Will the world buy the A400M?". Retrieved 17 November 2016 – via www.bbc.com.

- ↑ "The Airbus A400M Atlas – Part 2 (What is So Good about It Anyway) - Think Defence". thinkdefence.co.uk. 9 September 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Regan, James and Tim Hepher. EADS wants A400M contract change, adds delay>" Reuters, 9 January 2009. Retrieved: 1 July 2011.

- ↑ "Airbus A400M military transport reportedly too heavy and weak.' Thelocal.de. Retrieved: 20 July 2010.

- ↑ "Business: EADS denies mulling collapse of A400M project." Khaleejtimes.com, 23 January 2009. Retrieved: 20 July 2010.

- ↑ "Sascha Lange: The End for the Airbus A400M?". SWP Comments, 26 February 2009.

- ↑ Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose. "Airbus admits it may scrap A400M military transport aircraft project." The Daily Telegraph, 29 March 2009. Retrieved: 23 April 2010.

- ↑ Airbus-Projekt A400M droht zu scheitern, Der Spiegel, 2009-02-27.

- ↑ Engelbrecht, Leon. "SAAF considering A400M alternative". DefenceWeb, 3 April 2009.

- ↑ Reporter, Staff. "Govt cancels multibillion-rand Airbus contract". mg.co.za. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Brothers, Caroline. "Germany and France Delay Decision on Airbus Military Transport." The New York Times, 11 June 2009.

- ↑ "Factbox: The big money behind Airbus A400M talks." Reuters, 21 January 2010.

- ↑ "New chance for Europe's A400M transporter." Spacewar.com. Retrieved: 20 July 2010.

- ↑ "Airbus gets extension of A400M Contract Moratorium." Bloomberg News, 27 July 2009.

- ↑ "FT.com / Companies / Aerospace & Defence - EADS pleads for €5bn to complete A400M". archive.org. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Hollinger, Peggy, Pilita Clark and Jeremy Lemer. "Airbus threatens to scrap A400M aircraft." Financial Times, 5 January 2010.

- ↑ "Airbus chief 'may cancel A400M'." BBC News, 12 January 2010. Retrieved: 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "BBC News - Airbus' military plane continues to distract". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Bohlen, Celestine. "Airbus Needs U.S. Help to Dispose of Elephant."Bloomberg.com, 6 July 2009.

- ↑ "Review turns up the heat on eurofighter". Flight International, 22 July 2004.

- 1 2 Fulghum, D., A. Butler and D. Barrie. "Boeing's C-17 wins against EADS' A400." Aviation Week & Space Technology, 13 March 2006, p. 43.

- ↑ "U.K., France Seek Data on Super Hercules Plane, Lockheed Says." Bloomberg.

- ↑ Pocock, Chris. "Fresh doubts over A400M as Europe tightens its belt." ainonline.com. Retrieved: 9 September 2011. Archived 21 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Christina Mackenzie (1 January 2011). "Partner Nations Approve A400M Contract". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "Lords Hansard text for 24 October 2012 GC68". Hansard. UK Parliament. 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Felicity Morse (25 Oct 2012). "Lord Gilbert Slams Airbus A400M As 'Absolute Wanking Disaster' In Display Of Unparliamentary Language". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Merchet, Jean-Dominique (30 April 2013). "Armée de l'air : moins d'une quarantaine d'A400M devrait être commandée" (in French). Marianne.

- ↑ Stevenson, Beth (5 January 2016). "France reportedly confirms C-130J buy". Flightglobal. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ "French aerospace laboratory details A400M refuelling tests". FlightGlobal. 25 July 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus A400M engine glitch seen taking weeks to fix". Reuters. 5 April 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus Working A400M Manufacturing Glitches". Aviation Week. 4 April 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus Reports A400M Engine Gearbox Problems Will Cause Delays". Defense News. 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "Engine problems ground German A400Ms". IHS Jane's 360. 1 July 2016.

- ↑ Shalal, Andrea (9 July 2016). "Interim fix for A400M engine issue certified: Airbus". reuters.com. Reuters. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus wants to replace A400M parts after cracks found, Germany says". Reuters. 13 May 2016.

- ↑ "Germany Presses Airbus to Resolve A400M Problems". Defense News. 18 May 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus Works Through A400M Woes". Aviation Week. 1 July 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus Concedes Some A400M Problems Are 'Homemade'". Defense News. 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus Announces Additional €1B in Financial Charges for A400M". Defense News. 28 July 2016.

- ↑ "Airbus takes fresh €1bn charge against A400M". FlightGlobal. 27 July 2016.

- ↑ Kaminski-Morrow, David (17 December 2008). "Airbus A400M's engine becomes airborne for first time". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008.

- ↑ "Flying test bed". Archived from the original (Image JPG) on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ↑ "First A400M ferried from Seville to Toulouse". Airbus Military, 9 March 2009.

- ↑ "Second Airbus Military A400M completes maiden flight." Airbus Military, 9 April 2010.

- ↑ Hoyle, Craig. "Picture: Third A400M takes to the air." Flight International, 9 July 2011.

- ↑ "A400M wing passes critical test." defpro.com, 3 August 2010. Retrieved: 3 August 2010. Quote: A400M new airlifter has passed the ultimate-load up-bend test. Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "A400M close to first air drop, refuelling tests, says Airbus." Flightglobal.com, 31 October 2010.

- ↑ "Airbus To Ramp Up A400M Test Effort." Aviation Week, 28 October 2010.

- ↑ A high-profile parachute jump from the A400M airlifter. YouTube. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ Hoyle, Craig. "Picture: First paratroops jump from Europe's A400M." Flightglobal.com, 10 November 2010.

- ↑ Hoyle, Craig. "Fourth A400M nears debut, as type approaches 1,000 flight hours." Flight International, 17 December 2010.

- ↑ Tran, Pierre. "4th A400M Takes Off." Defense News, 20 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 Hoyle, Craig. "Bearing up: Airbus Military's 'Grizzly' nears civil certification." Flightglobal, 27 October 2011. Retrieved: 12 August 2012.

- ↑ Perry, Dominic. "A400M undergoes Swedish winter trials." Flight International, 8 February 2011.

- ↑ "The global tour of the A400M." Second Line of Defense. Retrieved: 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "A400M has high time in La Paz" Flightglobal, 30 March 2012. Retrieved: 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "Pictures." Ingeniøren, 16 April 2012.

- ↑ Hoyle, Craig. "A400M contract amendment signed, as test fleet passes 1,400 flight hours." Flight International, 7 April 2011.

- 1 2 Chuter, Andrew. "A400M Engine Wins Safety Certification." Defense News, 6 May 2011.

- ↑ Hoyle, Craig. "Pictures: New-look A400M readied for icing trials." Flight International, 16 July 2011.

- ↑ Morrison, Murdo. "Paris: Engine problems prevent A400M flying at show." Flight International, 19 July 2011.

- ↑ "Bearing up: Airbus Military's 'Grizzly' nears civil certification." Flightglobal. Retrieved: 2 May 2012.

- 1 2 Hoyle, Craig. "Soft ground cuts short A400M landing trials." Flightglobal, 25 May 2012. Retrieved: 7 June 2012.

- ↑ "Airbus Military A400M Receives Full Civil Type Certificate From EASA". defense-update.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ "Fourth Engine for A400M Brings First Flight Closer". Reuters, Archived 9 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Static test programme begins on aircraft MSN 5000". EADS, 28 March 2008. Archived 8 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "A400M Countdown #4 – A Progress report from Airbus Military." A400m-countdown.com. Retrieved: 20 July 2010.

- ↑ "El Rey estrena el Airbus 400, el mayor avión militar de fabricación europea." ELPAÍS.com.

- ↑ "A400M Gets Going". 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012.

- ↑ "French acceptance sees A400M deliveries take off". Flight International, 1 August 2013.

- ↑ "France formally accepts A400M transport". Flight International, 30 September 2013.

- ↑ "First Airbus Military A400M for Turkish Air Force makes maiden flight". EADS. 12 August 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 Waldron, Greg (10 March 2015). "Malaysia receives first A400M". Flightglobal. Reed Business Information. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ "A400M Countries Form Monitoring Team, Germany Warns Of Airlift Gap". Aviation Week. 21 May 2015.

- ↑ M. J. Pereira (10 May 2015). "El A400M accidentado comunicó problemas en el tren de aterrizaje tras despegar". ABC de Sevilla.

- ↑ "UK halts Airbus A400M usage after Seville crash". 10 May 2015.

- ↑ "Black Boxes of Crashed A400M Plane Found, Aircraft Grounded". 2015-05-10.

- ↑ "Software Cut Off Fuel Supply In Stricken A400M". Aviation Week. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ "A400M probe focuses on impact of accidental data wipe". Reuters. 9 June 2015.

- ↑ "Airbus Says 3 of 4 Engines Failed in Spain A400M Crash". Defense News. 27 May 2015.

- ↑ "Airbus can restart A400M test flights in Spain after crash: Defense Ministry". Reuters. 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Airbus hoping to resume A400M deliveries". Financial Times. 17 June 2015.

- ↑ "Airbus resumes A400M customer deliveries". IHS Jane's 360. 22 June 2015.

- ↑ "France receives first A400M with tactical capability". FlightGlobal. 22 June 2016.

- ↑ "The versatile airlifter for the 21st Century." Airbus Military. Retrieved: 2 May 2012.

- ↑ "A400M Capabilities." Airbus Military. Retrieved: 15 May 2010. Archived 7 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "Pilot Report Proves A400M's Capabilities". Aviation Week. 10 June 2013.

- ↑ Military Aircraft Airbus DS | A400M. Airbus Defence & Space. Retrieved: 19 May 2015

- ↑ "Airbus Military." countdown.com.

- ↑ "IR Sensors Page 4 English Seite 5 deutsch. IAF.Fraunhofer Archived 31 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "EADS and Thales to supply latest-technology missile warner to A400M." globalsecurity.org.

- 1 2 "Military Aircraft Airbus DS – A400M". airbusmilitary.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ Klimek, Chris (1 April 2015). "Tom Cruise Hangs on to a Flying Airbus (Really) in the Next Mission Impossible". airspacemag.com. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ "Airbus A400M tactical airlifter makes combat debut in Mali". The Aviationist, 2 January 2014.

- ↑ Hoyle, Craig (6 January 2014). "French Mali mission gives A400M operational debut". Flight International. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ "A400M Deliveries Create Headaches For Uk". Aviation Week. 11 September 2015.

- ↑ "EADS welcomes South Africa's intention to become an A400M partner". EADS, 15 December 2004. Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "South Africa signs for A400M transports." Flight International, 3 May 2005.

- ↑ Roberts, Janice. "Airbus refunds A400M payments to Armscor." Moneyweb, 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Airbus Military signs agreement with Chile Airbus Military. Archived 6 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Chile to Buy 3 Airbus A400M Transports." Defense Industry Daily. Retrieved: 29 March 2013.

- 1 2 "Annual Report and Registration Document 2005." European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company EADS N.V., December 2005 Retrieved: 25 April 2011

- ↑ "A400M price tag stays at RM600m each." Malay Mail, 13 November 2009. Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Retrieved: 30 October 2016.

- ↑ "Durchbruch im Streit über A400M" (German) Sueddeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved: 27 October 2010.

- ↑ "Germany to take fewer A400M planes." AFP, 28 January 2011.

- ↑ "La France a réceptionné le premier Airbus A400M" (French) Le Figaro. Retrieved: 2013-08-01.

- ↑ "More A400M Delivery Delays Expected In 2015". Aviation Week. 20 January 2015.

- ↑ "Spain receives its first A400M transport". flightglobal.com. 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Evaluación de los Programas Especiales de Armamento (PEAs)" (in Spanish). Ministerio de Defensa, Madrid (Grupo Atenea), September 2011. Retrieved: 30 September 2012.

- ↑ "Spain aims to resell half A400M fleet." Reuters. Retrieved: 2 August 2013.

- ↑ Reed Business Information Limited. "UK's first A400M arrives at Brize Norton home". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ UK approaches Airbus Military, Thales for A400M training service August 2010 flightglobal.com

- ↑ "Airbus Defence and Space delivers A400M to Turkish Air Force". airbus-group.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Turkey Accepts First A400M" Defense news Retrieved: 11 May 2014.

- ↑ "Military cargo plane to be delivered to Turkey in 2013." Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved: 1 July 2011.

- ↑ "Turkey accepts delivery of its First Airbus A400M". 5 April 2014.

- ↑ "Turkish air force receives second A400M" Flightglobal. Retrieved: 2014-12-30.

- ↑ "168-million-euro military plane to touch down in Luxembourg in 2019". Luxemburger Wort. 23 January 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Marhalim Abas (15 June 2016). "Malaysia Receives 3rd A400M, 4th And Final Due This Year". Aviation Week Network. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Osborne, Tony (9 May 2015). "Airbus A400M Crashes During Test Flight". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- ↑ "Four dead after military plane crash in Spain". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 16 December 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ Alexander, Harriet (9 May 2015). "Video: Military plane crashes during test flight near Seville". Telegraph. London.

- ↑ Teresa López Pavón (9 May 2015). "Cuatro muertos tras estrellarse un avión militar A-400M en pruebas junto al aeropuerto de Sevilla". ELMUNDO (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Fatal A400m crash disrupts production-recovery plan". Irish Times. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ "Airbus A400M military transporter crashes on test flight, killing four". Reuters. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ "Fatal A400M crash linked to data-wipe mistake". BBC. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "A400M Specifications." Airbus Defence & Space via militaryaircraft-airbusds.com. Retrieved: 15 July 2015.

- ↑ "Airbus Military A400M". Jane's All the World's Aircraft. Jane's Information Group, 2010. (subscription article, dated 24 February 2010).

- ↑ EASA Type Certificate Data Sheet for A400M-180

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Airbus A400M. |

- Airbus Military A400M page

- OCCAR site

- BBC video of unveiling of the A400M

- Official unveiling in Seville

- Cutaway diagram