Emma Woodhouse

| Emma Woodhouse | |

|---|---|

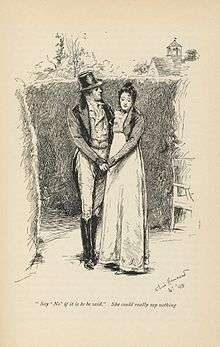

'_(11299328635)_(cropped).jpg) Emma in an illustration by Hugh Thomson from an 1896 edition of the novel | |

| Full name | Emma Woodhouse |

| Primary residence | Hartfield |

| Family | |

| Romantic interest(s) | George Knightley |

| Parents | Mr. Woodhouse (father) |

| Sibling(s) | Isabella |

Emma Woodhouse is the 20-year-old protagonist of Jane Austen's novel Emma. She is described in the novel's opening sentence as "handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and a happy disposition." Jane Austen, while writing the novel, called Emma "a heroine whom no-one but myself will much like."[1] Emma is the richest of Austen's heroines.

Emma is an independent, wealthy woman who lives with her father in their home Hartfield in the English countryside near the village of Highbury. The novel concerns her attempts to be a matchmaker among her acquaintances and her own romantic misadventures.

Emma professes that she does not ever wish to marry (unless she falls very much in love), as she has no financial need to, having a large inheritance and she doesn't wish to leave her father alone. After series of new engagements, visits at Highbury and lots of miscommunication, Emma finds herself falling in love with her friend George Knightley.

Personality

Emma often behaves in a frivolous or selfish way, and shows a lack of consideration for her friends and neighbours. She carelessly manipulates the life of her friend Harriet Smith, neglects her acquaintance Jane Fairfax, and insults the poor and dependent Miss Bates. However, her friends, especially Mrs. Weston and George Knightley, see potential in her to improve herself and become a better person.

Relationships

George Knightley is Emma's friend, brother-in-law of her sister Isabella, and ultimately her love interest. At 37, he is significantly older than she and Emma looks up to him. He often gives her advice and guidance, particularly since Emma's mother is deceased. Mr Knightley has a strong moral compass and frequently teases or scolds Emma for her more frivolous pursuits, such as matchmaking. He also disagrees and argues with Emma on occasion, notably on Emma's interference with Harriet Smith and Robert Martin's relationship. Knightley spends most evenings with Emma and her father, taking the short walk from his home to theirs.

Due to his attachment to Emma, Mr Knightley has disliked Frank Churchill (unconsciously labeling him as competition)[2] even before he met Frank, and remains doubtful of him even when everyone else indulges the younger man. It is also his jealousy of Frank that causes Mr Knightley to acknowledge his romantic feelings for Emma. Although he is mostly rational, he can also act more impulsively at the cause of Emma, such as making a sudden visit to London and returning in an equally unexpected manner to propose to her. Emma, too, gradually realizes her feelings for him due to her jealousy first of Jane Fairfax and later of Harriet Smith.

Harriet Smith is a low-born and poor pupil at the local boarding school, of whom Emma takes notice after she loses the companionship of Mrs Weston. Despite Harriet's humble origins, Emma admires her sweetness, good nature, and pleasant looks. Emma decides to take Harriet under her wing and help her find a good husband. However, Emma's pride prevents her from seeing a good match for Harriet in the person of Robert Martin, a respected farmer and the initial and ultimate romantic interest of Harriet. Instead, Emma encourages Harriet to foster affections for Mr Elton, the village vicar, which ends disastrously. However, naive Harriet does not blame Emma for her mortification, and the two remain friends.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Emma, Harriet develops a crush on Mr Knightley after he asks her to dance when Mr Elton has refused to. Emma, who believes that Harriet holds a secret regard for Frank, says that she should not give up hope because there have been many other happy though unequal matches. When Emma discovers the truth, she is both appalled and dismayed, which leads to her revelation that she is in love with Knightley. Mrs Elton's relationship to Jane Fairfax parodies Emma's relationship to Harriet.

Mr Woodhouse, Emma's father, is a valetudinarian and is so paranoid about his own and others' health that he is nearly helpless. He is against eating cake, going outside, attending parties, and getting married, among other things, on the grounds that these might damage the health. As a result, Emma takes on the role of caretaker for him, as he is incapable of exerting parental influence or even taking care of himself. Mr Woodhouse is fond of and attached to his daughters, who are likewise affectionate toward him. With Isabella married, Emma took it upon herself to remain at Hartfield and take care of her father. Emma's consideration towards her father is one of her redeeming attributes.

Mrs Weston, formerly Miss Taylor, was Emma's governess before she married Mr Weston. She and Emma love each other and are close friends. She serves as a mother figure for Emma and often gives her advice. Emma admires Mrs Weston as wise and virtuous, and looks up to her. When Mrs Weston marries, Emma becomes lonely and therefore seeks the companionship of Harriet Smith, a friendship which Mrs Weston approves of although Mr Knightley does not. Mrs Weston initially wished for a match between Emma and Frank Churchill and saw a potential attachment between George Knightley and Jane Fairfax, but ends up surprised by but delighted with the ultimate outcome.

Jane Fairfax, orphaned at a young age, is Miss Bates' niece. She is a beautiful, accomplished young woman, who represents everything that Emma should be. Jane is the ideal companion for Emma. However Emma neglects her due to jealousy, yet claims it is because Jane is 'cold'. Unbeknown to Emma, Jane is secretly engaged to Frank, and therefore Emma's flirtation with Frank causes Jane great pain.

Notable portrayals

- Doran Godwin in the 1972 TV serial

- Alicia Silverstone as Cher Horowitz in the 1995 film Clueless

- Gwyneth Paltrow in the 1996 film

- Kate Beckinsale in the 1996 British film

- Romola Garai in the 2009 BBC TV serial

- Sonam Kapoor as Aisha Kapoor in the 2010 film Aisha